An Essay on the Conduct of the Passions and Affections. with Illustrations on the Moral Sense.

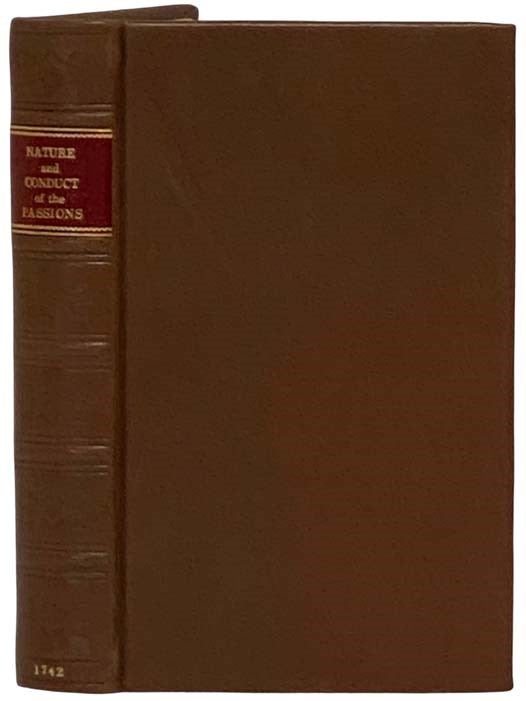

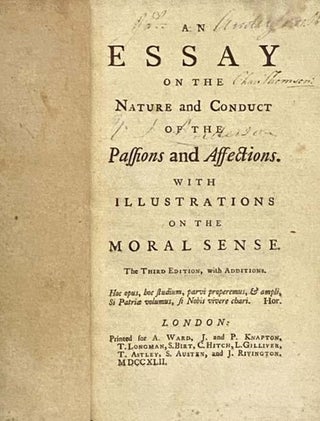

London: Printed for A. Ward, J. and P. Knapton, T. Longman, S. Birt, C. Hitch, L. Gilliver, T. Astley, S. Austen, and J. Rivington, 1742. Third Edition. Full-Leather. Very Good / No Jacket. Item #2329643

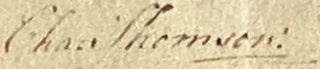

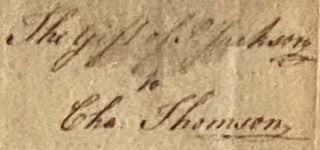

Third edition, with additions. ESTC T61185. Rebound in modern full leather with red spine label, gilt titles and rules, new end sheets. Ink gift note on front flyleaf ('The Gift of P. Jackson to Chas. Thomson') and several ink names (including Thomson's, and two that both appear to be Andersons, but are difficult to discern) on title page. Charles Thomson was an Irish-born patriot leader in revolutionary America, and secretary of the Continental Congress - in this capacity, his name and John Hancock's were the only two to appear on the first draft of the United States Declaration of Independence. Thomson was also an associate of Benjamin Franklin, and a member of Junto, the organization which later became the American Philosophical Society. An important work with an exciting provenance. Margins faintly stained on a few pages, front and end matter lightly foxed, but surprisingly tight and clean throughout.

xx, [4], 339 pp. Hutcheson's works influenced those of David Hume and Adam Smith. Gladys Bryson in Man and Society (1945) was probably the first modern scholar to contend that Francis Hutcheson was the 'father' of the Scottish Enlightenment, a view confirmed by Charles Camic in Experience and Enlightenment (1983): "His celebrated proclamations on economics, politics, psychology, and ethics challenged a solid phalanx of received wisdoms and anticipated many of the specific arguments... of Hume and Smith." Hutcheson's "first philosophical work [was] An Inquiry into the Original of our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue (1725). In the first of the two treatises contained in the Inquiry he argued that there is an internal sense, analogous to the five external senses, which brings to mind ideas of beauty, order, harmony, and design, whenever one perceives objects, artefacts, scenes, and compositions which exhibit uniformity amid variety. In the second treatise he argued for the presence in human nature of a moral sense which determines one to recognize virtue whenever one observes a character or an action prompted by benevolence or kind affection. He found no merit in arguments which reduce virtue to self-interest, however useful or serviceable to others such interested conduct might appear. 'If there be any Benevolence at all, it must be disinterested; for the most useful Action imaginable, loses all appearance of Benevolence, as soon as we discern that it only flowed from Self-Love, or Interest' (p. 129). His argument that the moral sense forms a natural or instinctive part of human nature was directed pointedly against the contention of Bernard Mandeville that virtue and vice are artificial distinctions, the inventions of politicians, who employ these terms for no other reason than to curb the appetites and ambitions of unruly subjects. Hutcheson's Inquiry provoked an extended, mutually respectful exchange with the Revd Gilbert Burnet (1690–1726) in the London Journal (April–December, 1725). Burnet (using the pseudonym Philaretus) argued that Hutcheson's determination to ground moral distinctions upon sensibility and feeling left moral life without an adequate foundation. He proposed that antecedently to any sensation or feeling of virtue there must be a reason or a rational apprehension of goodness and rectitude. Hutcheson (writing as Philanthropus) countered that in order for the terms reason, reasonable, and rational to be meaningful they must refer to the happiness of persons or moral agents; an individual who prefers his own happiness to the general or public happiness might be considered reasonable but he could not be considered moral; one who prefers the greater or public happiness to his own happiness is properly considered not only reasonable but also moral or virtuous. The latter judgement cannot be based upon reason: it must derive from a still more basic feeling that benevolent or public-spirited action is singularly or particularly virtuous." (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography) Hutcheson later expounded upon his philosophical system in the posthumously published 1755 work A System of Moral Philosophy.

Price: $3,500.00