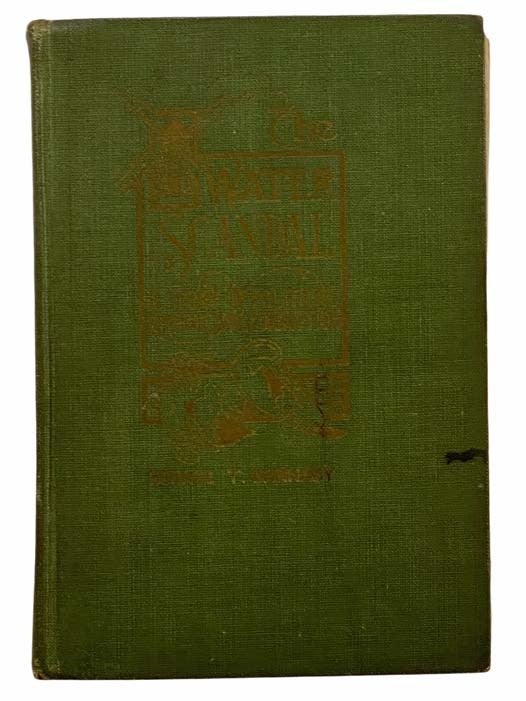

The Water Scandal: A Story of Political and Municipal Graft and Corruption

Grand Rapids: Shaw Publishing Company, 1910. First Edition. Hard Cover. Good / No Jacket. Item #2308539

First thus. Former library copy with usual marks. First gathering slightly sprung, indicating it may have been repaired at the binding at some point.

325 pp. A novel about political corruption, originally published under a different title in 1908 (see below). The original title still appears as the header on the text pages of this edition. "Horace T. Barnaby was born in North Star Township, Gratiot County, Michigan... He worked as a schoolteacher before graduating from the University of Michigan Law School in 1902. After graduation, he worked as school inspector, township clerk and supervisor of Kent County. He also dabbled in creative writing, and in 1908, Barnaby published a book entitled 'The Decade: A Story of Political and Municipal Corruption.' Set at the turn of the century, the book details the story of how a man was falsely accused of being involved in the Grand Rapids 'Water Scandal.' A staunch Republican, Barnaby entered into politics as a member of the Michigan state house of representatives from Kent County 2nd District from 1901 to 1904. From 1907-1908, he continued his career as a delegate to Michigan state constitutional convention of the 17th District. Barnaby was a State Senator from 1909 to 1913. In addition, he was a candidate in the primary for Lieutenant Governor of Michigan in 1938 and 1940." (Michigan official directory and legislative manual, 1903, pg. 789) "As Grand Rapids, Michigan neared the end of the nineteenth century, the growing city looked for a new water supply. The personal interests of the city's leaders quickly overwhelmed the common good. Corrupt schemes quickly developed. As backroom deals came to the city's attention, the Grand Rapids water scandal blossomed. The water scandal was not the city's first instance of corruption, but rather the first genuine scandal. Previous scandals had left few lasting marks. Connected socially and financially, the city's elite became caught in the middle of the scandal as business partners, political rivals, and neighbors landed on opposite sides. These complications slowed the pace of reform. Even after years of occupying headlines and courtrooms only two men ever served prison time for their involvement. Most of the men involved remained politically and socially active after the scandal. However, the water scandal began the transition between Gilded Age politics rooted in personal connections and Progressive politics centered around impartial administration. The water scandal provided the necessary atmosphere for reform-oriented movements to grow, reaching a height in 1917 with the creation of the city's commisioner-manager system. In 1898, new Mayor George Perry pushed for a new source of fresh water. Early in his second term, two years later, the city's Common Council, its legislative body, took concrete steps towards securing a new water supply. The city's leaders debated a variety of methods, but one quickly gained popularity. A plan to build a pipeline from Lake Michigan to Grand Rapids (roughly forty miles of pipe) became the choice of many of the city's leadership, despite the millions of dollars necessary to complete the project. By October of 1900, the city's Common Council seemed ready to award a contract for the pipeline to one of two bids. To demonstrate the ability to build the multimillion dollar water system, the bids submitted checks for $100,000. At the meeting, however, Perry dramatically revealed both bids were forgeries. Despite the dramatic news, city leaders decided to simply reopen the bidding process. Phony bids were just part of the process. Before the city could award the contract, more shadowy actions came to light. In February of 1901, Chicago police arrested city attorney Lant Salsbury for stealing $50,000 dollars from an Omaha capitalist. The money was allegedly for Salsbury to bribe politicians and secure the water contract. Though Cook County dropped the charges shortly after Salsbury returned the money, the foundation of the water scandal had been laid. Seeing a political opportunity, Grand Rapids Republicans ran a campaign touting their trustworthiness in juxtaposition to the Democratic Salsbury. While effective in adding a couple of Republican seats on the Common Council, the legislative body voted to retain Salsbury along partisan lines. When Salsbury escaped political punishment, the need for legal action became urgent. A Kent County grand jury investigated the rumors of other bribery schemes and indicted five men in June 1901. In addition to Salsbury, the grand jury also indicted Henry Taylor, a young New York millionaire who provided the money, Stilson MacLeod, a local banker who moved the cash, and Thomas McGarry, a local attorney who had put Salsbury in contact with the men running the scheme. The main organizers, con-men Frederick Garman and Robert Cameron, however, did not face any charges after cooperating with the grand jury. The scandal stayed small until 1903, when Salsbury completed a sentence for a federal banking violation and faced additional prison time for bribery. Given limited options, Salsbury became the prosecution's star witness. The legal system, however, struggled to implement reform as many early trials including Salsbury's and the then-former mayor George Perry faced procedural issues. Several defendants' appeals reached the state supreme court. The legal system was admittedly rusty in pursuing punishment. Five years after the water scandal emerged, the prosecution no longer believed they could convict anyone. The water scandal ended quietly. In February 1906, the prosecuting attorneys dropped all open cases, including the case against George Perry. The city's residents had become, as historian Z. Z. Lydens phrased it in The Story of Grand Rapids (1966), "weary if not yet quite bored." Despite the pervasiveness of the water scandal's bribery, only Salsbury and McGarry served any prison time. However, the city had exerted genuine effort to challenge corruption. Before the water scandal, the city only nominally took care of other scandals, if not completely overlooked them. The Grand Rapids water scandal reveals the manner in which many smaller cities moved from municipal governments centered on personal relations and social connections, to a more Progressive government led by professional managers and their administrations. The city's elite, though intimately involved in the scandal, remained. No political machine dismantled. No dominant family displaced. Grand Rapids made the transition to Progressive-style government gradually. The water scandal was the first step." (Brian Sarnacki, "The Water Scandal," Corruption and Reform, 2015)

Price: $125.00